Competitive Muay Thai is about one thing and one thing only. That is to win the fight! Taking second place to this maxim, is to hit the opponent without being hit yourself. It is as simple as that. However, there are many boxers about (and this I address to their Coaches and Teachers) who hope this will happen by good luck, rather than by good management.

It doesn’t happen like that if your opponent has superior technique, stamina and ring craft. In this post I want to go into, albeit briefly, the important aspects of ring craft.

Read, enjoy and use constructively the contents of this post in your training regime and if you have any queries get in touch.

Acquiring an extensive repertoire of techniques: punches, elbows, knees, kicks and clinch work, is pointless, unless the boxer can then apply those skills in the context of fighting in the ring.

If you’re not aware of the positive aspects of fighting in an enclosed space, then the ring is going to be the scariest place on earth when you climb into this new environment for the first time.

You must be aware of these positive aspects, understanding thoroughly how and when to use the ring in a constructive way within the framework of your technical competence.

All skill work must be related to the ring. In the ring you must be able to out think and out manoeuvre your opponent, turning a defensive move into an offensive one and even utilising the ropes when in the clinch. More of this in a future post.

After the initial performance of the Ram Muay, where the fighter asserts his authority in the ring (by demonstrating balance poise and confidence), you reassert this authority by taking the fight to the opponent. You can do this by being the first to the centre of the ring after seconds are called away, and the first to move in on the opponent when the referee calls “Chok”.

Thus you are therefore at a psychological and physical advantage in the initial stages of the fight. This approach has many positive aspects. The opponent is immediately taken by surprise and as well as being physically threatened, is psychologically shaken too. You must continue to maintain authority by keeping up this pattern of behaviour, and you now have only your fitness and technical ability to rely on.

Control of the fight is generally dictated by three things: rhythm, planning and form.

Each boxer has his own rhythm, a basic rhythm of work that will dictate his style. This is of course also dictated by his level of fitness and the ability of his coach. If a boxer understands this principle, he can set up a rhythm with his opponent, break it and then pick out the openings in his opponent’s defence. It is then up to the boxer to exploit these areas of weakness and take control.

Each fighter has a plan of campaign, and even the most hopeless of boxers has a basic idea of what they want to achieve. We base this upon the boxer’s build, style, fitness and temperament.

The successful boxer is one who can adapt the campaign plan to suit each fight. All sparring has a form, a movement pattern, and this involves the relative positions and movement of the fighters around the ring. Control of this space is the foundation for winning the fight.

Dominating the centre, cutting the opponent off at the angles, lateral movement with angular attacks and constant changes of direction, all serve to upset the opponent’s tactics, plans and rhythms.

Ring craft is all about creating openings, and scoring is about taking advantage of these openings. An essential part of training and fighting in the ring is the ability of the fighter to draw his opponent. Feinting attacks do just that and, of utmost importance to the Thai fighter, is the obvious use of clinch work. When boxing it is important to develop skill in being unpredictable, always trying to keep the opponent wondering what is going to happen next.

Constant movement of the feet and hands, and the use of replacement or skip steps, or even just standing still, all serve to confuse the opponent. These strategies keep them guessing. Once you set up this approach, notice how it will affect the opponent. It’s like a game of chess, just a little tougher!

Learn how to trigger the opponent’s response so you can take advantage of any openings that this might create.

Always ask yourself:

What are the opponent’s mannerisms?

What is his style?

Does he defend well, and what is his favourite method of attack?

We should practice these strategies back in the gym. However, it’s important to note that training in the gym is only a preparation for the real thing.

It is sadly true to say that sparring in the gym has an air of predictability about it. The atmosphere is safe and secure. If you spar with your fellow boxers you are already adept at reading them and can therefore exploit their weaknesses easily. You train with them enough to know how they behave. But when you face a stranger, well, it’s very different.

This is why it’s important to work on the psychological aspects of the fight game.

Having a clear mind is always preferable to having one cluttered with fears and doubts. Learn how to do this quickly and confidently. I have a huge amount of resources available for those who may be interested in this aspect of the martial arts.

Sparring in the gym is an opportunity to rehearse the following skills.

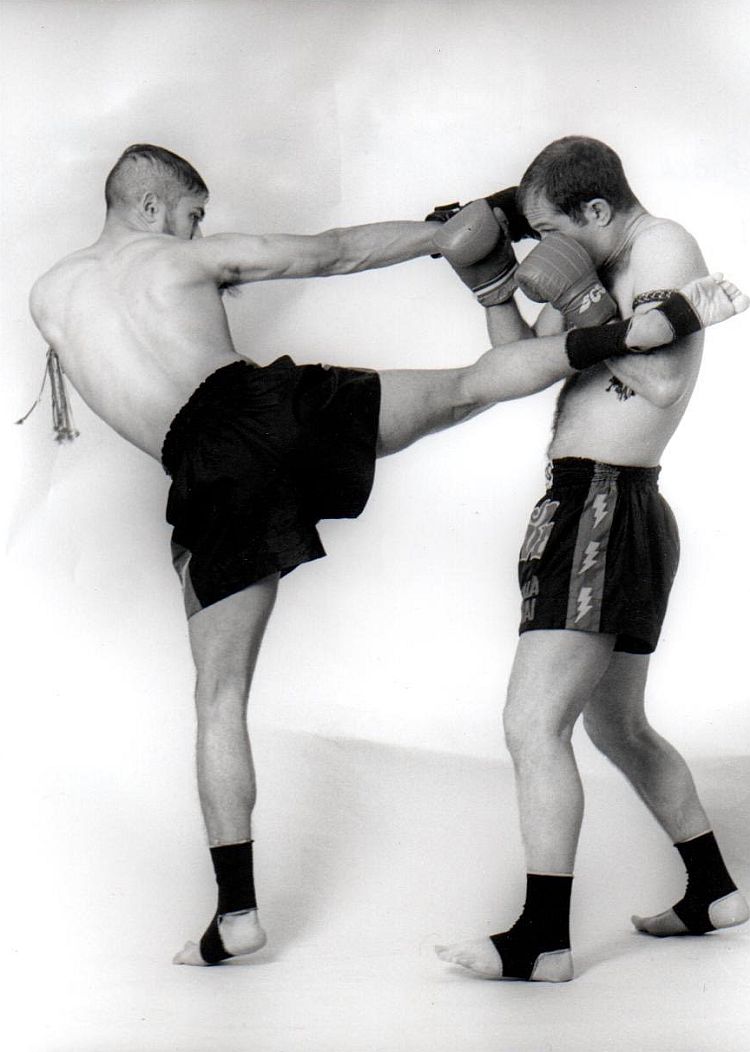

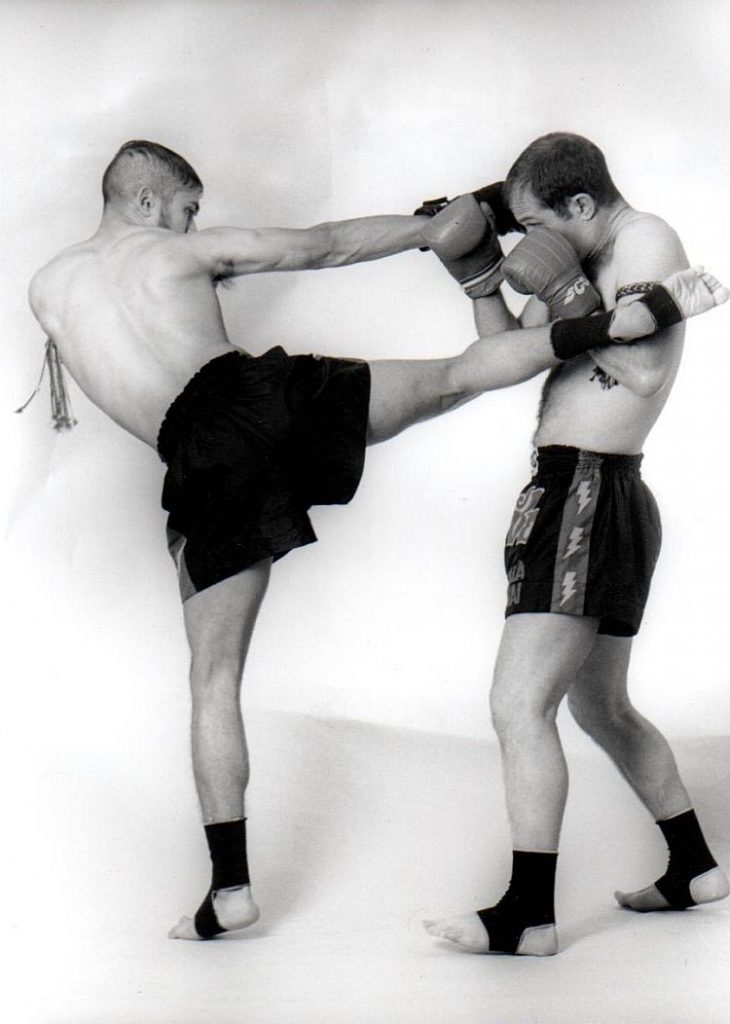

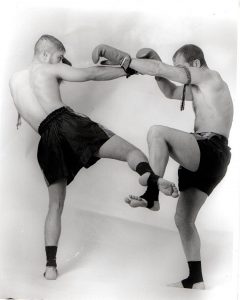

Feinting, by definition, is the technique of making an opponent think something is about to happen, or is happening. You then do something unpredictable and thus the feint works!

Feints are done using:

1) Sudden foot work changes as in the replacement Step

2) Kicks and knees. Feint in One Direction and then change legs or technique, i.e. front kick to round house.

3) Hands and elbows. Feign a jab then change to a close elbow strike with the same hand.

4) Clinchwork. Pull first in one direction and then suddenly change direction and sweep the opponent.

Naturally it is possible and indeed necessary to learn to combine all the above elements. It is often the case that a quick movement of the trunk or shoulders can also fool the opponent into believing an attack is coming.

Essentially, the feint has three phase:

a) FEINT

b) RESPONSE by the opponent

c) YOUR ATTACK the counter to the counter

Mind you, they don’t always work, so expect the unexpected! The opponent may feign surprise from your feint in order to set you up for their attack. If this sounds complicated, well welcome to sparring!

Another aspect of feinting is the drawing in of the opponent, and this usually means deliberately exposing a target and waiting for the attacker to come charging in. We must make careful consideration of:

a) Distance

b) Confidence

c) Footwork

Obviously distance and footwork are mutually inclusive and should be practised regularly in the gym on the pads, bags and in sparring practice.

An example of drawing would be to drop your lead hand, step across the incoming opponent with a low roundhouse kick, which he may then block which you then counter immediately with a right cross to the jaw.

In summary, I would like to leave you with a few tips.

- Have confidence in your abilities

- Position of the head and eyes is vitally important in the clinch and when moving in on the opponent

- Attacks should be varied from upper body to legs constantly

- Always vary the angle of attack

- Set up a rhythm and a pattern,then break it.

- Depth of stance is important for the generation of power from a feint

- Be psychologically and physically prepared

- Finally you must control the fight. Take the fight to the opponent and until next time…

TRAIN HARD, FIGHT EASY!